Dec 12- Dec 18, 2002

|

|

||||

|

|

One man’s forest Lee Altenberg is digging out “Walmart weeds” and putting in aeia. Using a computer to save the past.

Right in his own backyard, in a scrubby gulch a couple of blocks from his house, one Kihei man is busy planting a forest. In this personal ecology project, University of Hawaii Associate Professor Lee Altenberg is putting back the plants and trees that more than a century ago were thriving in that dry, hot country, covering the flanks of Mt. Haleakala, from the mountain top to the sea. Altenberg is a computer science specialist at UH Manoa and a Kihei resident. Liilioholo Gulch — which is actually not much more than a ditch — is just one of many mountain-top-to-sea drainage channels that collect and move storm waters when heavy rains hit the mountain Southern flank. This particular ditch drains into the ocean at Kamaole Point. Through the years it’s filled up with heavy mats of grasses and haole koa. Altenberg is digging out these invading species and has planted and is nurturing 20 to 30 endangered heritage plants that he said have been crowded out over the years by cattle, development and vigorous “Walmart type” alien species. Altenberg is trying to recreate the Hawaii of old, right there in this gulch. He described his effort as trying to “use the computer to save the ecology.” Back 1,000 to 1,500 years ago, he said, the slopes of Haleakala, from the mountain top to the sea were green with dense, multi-story forests, and the earth carpeted with ground cover. “Birds all over the place, red and green songbirds warbling overhead, great, big earthbound birds, some as high as your head, running thru the trees, raising their chicks.” The first Hawaiians to land here “ate them up,” he said. “Probably pretty quickly. But, times past, this was a Bird Kingdom.” Scientists have found their bones, so there’s concrete evidence the big birds once lived here. It could be somewhat that way again, Altenberg eagerly suggested. “If eventually neighbors got together and planted their yards with the old plants, worked on the gulches — which now are the only remnants of the old forest down here at sea level. We could restore a lot of that.” Realistically, he knows that with modern development in place, it could never be wall to wall forest the way it was, when, U.S. Geological Survey research biologist Walt Medeiros said, “you could walk from Olowalu to Makawao without ever getting in the sun.” Now, those trees are practically gone. |

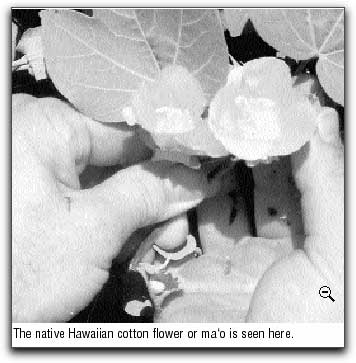

A couple of miles or so up the southern flanks of the mountain, there are still a couple pieces of the ancient dry land forest left—about 1,300 acres (the Auwahi tract), above Ulupalakua, and 237 acres (Pu‘u O Kali), upslope from the Pi‘ilani Highway. Even these are just “museums,” Medeiros said, because for years they have not produced seedlings for future growth. Work is in progress on these remnants, with Medeiros and his band of volunteers in the restoration vanguard. Ten acres of Auwahi has been fenced and planted and is being tended, and fencing of Pu‘u O Kali will begin soon. In fact, Altenberg has been one of the working volunteers at Auwahi. Besides, he’s been serving on a dozen different local restoration projects, including the saving of the highly endangered po‘ouli bird. But Liilioloho Gulch is Altenberg’s own individual work place. A number of his plants have grown to be way over his head now. Before starting work, he had, of course, talked with several of his neighbors about the proposed project and had permission from four of them to plant and beautify the slope below their developed yards. (Their property rights extend into the gulch). Later he plans to approach other residents to see whether it’s all right to extend his plantings. Among the plants he’s gotten started are naio — a tree with tiny white flowers that smell like honey; the very rare aeia tree; ma‘o, the Hawaiian cotton with bright yellow flowers; ilima, with pretty flowers, that can serve as a ground cover; ilie‘e, one of a dozen soft ground covers. A few old Hawaiian plants were already in place when he started the project, including a tall “true” wili wili tree, probably grown from seeds that had washed down the mountainside. He found Hawaiian tobacco, and kept it alive because it provides food for the rare Hawaiian sphinx moth. Altenberg’s computer science work involves investigating the theoretical foundations of evolutionary computation and evolutionary processes, “including genetic algorithms, genetic programming, and theoretical population genetics… employing both mathematical analysis and computational experiments to discern the workings of algorithms based on Darwinian selection…” He’s able to work from his home in Kihei, where he and his father, Roger Altenberg, retired professor of theater at California State University, Los Angeles, share a house. Alternberg first determined he would be a scientist when he was about seven and listened to his mother explaining the solar system with the help of a model made out of grapefruits and oranges. At first he headed for astronomy, then in the direction of nuclear physics, later going into computer science with its promise of making discoveries that would help the world’s living conditions. His dream of great big forests in Kihei may sound pretty ambitious, but if you find yourself wanting to help do that, you might start by contacting the Maui Botanical Gardens at 249-2798, where Lisa Schatten-berg Raymond can put you in touch with nurseries that can supply plants, and with other sources of information. However, no matter what we do, it seems unlikely that those big birds that once roamed the Kihei forests will make a reappearance. But a restored native mountain forest could cause other mircles to follow. n

|

||