Beyond Capitalism:

Leland Stanford’s Forgotten Vision

Published in Sandstone and Tile, Vol. 14 (1): 8-20,

Winter 1990, Stanford Historical Society, Stanford, California.

Original version © 1990, revisions © 1995-2021 by Lee Altenberg.

[Cover art]

[Original PDF]

Labor can and will become its own employer

through co-operative association.

— Leland Stanford

Buried in the stacks of the Stanford University Archives is a secret about Stanford’s history that has been kept for decades. It is not the kind of secret that needed anyone to keep it hidden; rather, it is a “public secret”—a piece of history that our society, by the very nature of its development over the last 100 years, was likely to erase from its transmitted memory.

Even that great conservator of history, the university, can be party to this erasure when its history departs from the contemporary narrative it wishes to project.

Leland Stanford was one of the “Big Four” — the owners of the Central Pacific Railroad, and by mid-century he had amassed a fortune of many millions of dollars. When one spoke of a “Robber Baron” in the 1880s, Leland Stanford would be among the first names to come to mind. Yet during the final decade of his life, Leland Stanford had come to the conclusion that American society would in the future be better off if it did not create more tycoons such as himself; that the industries of American should instead come to be owned and managed cooperatively by their very workers, and the division between capitalist and laborer disappear. This, as Stanford saw it, would be a fulfillment of the dream of American democracy.

This idea did not originate with Leland Stanford. In the 1880s, the vision of a cooperative commonwealth—a system of worker-owned cooperatives—moved from the margins of politics to form the core of a mass political movement in the United States, the Populists, which was at its zenith. And Leland Stanford, citing his personal experience and applying his most forceful arguments, became a champion of the vision.

The Populists (involving millions of southern farmers and northern industrial workers) were the last mass movement in the United States to comprehensively challenge the growing domination of society by burgeoning corporations. From today’s vantage point, we may identify the labor movement as the home for such political aspirations. This, however, is a misconception; the “labor movement” emerged after the defeat of the Populists in the 1890s, and was far more narrowly conceived than the Populists’ ambitions: it accepted a social contract that gave corporations the role of initiator and controller of employment, production, services, and capital. The labor union movement, in contrast to the Populists, sought merely to give workers better contracts within this structure of control. In American history since the defeat of the Populists, the idea of worker ownership of corporations has been relegated to the margins of political debate and creativity, a niche so marginal that from our vantage point of the 1990s, the idea sounds socialistic, utopian, or simply quaint.

In 1885, however, when Leland Stanford became a United States Senator and founded Stanford University, worker ownership of industry seemed neither utopian nor quaint. It was a widely discussed idea for averting the escalating crises between corporations and workers that appeared at that time to be headed toward an ominous denouement. Worker ownership of industry was seen as a good idea which needed to be tried, and America was seen as a society free enough that it could be tried. The Populists hoped therefore that the steady replacement of corporations by worker cooperatives could be achieved. The goal of the “seizure of State power” advocated by the communists in Europe was alien to this movement. Cooperatives were seen not as an end to free-enterprise, but as a freeing of enterprise for common people from domination by the “plutocracy” of wealthy industrialists.

While the idea of worker cooperatives may seem to the contemporary reader an interesting, if impractical, ideal, during the Populist movement it formed the foundation for hope in the daily lives of hundreds of thousands of people.

Should today’s social contract ever fail on a large scale, one can expect that ideas from the margins (crazy as well as rational) will flow into the center as people become more receptive to novel solutions for the society’s woes. It is therefore prudent to maintain the “germ lines” of social thought, much as horticulturalists maintain heirloom plant varieties for the day when their genetic endowments may prove useful. The story of Leland Stanford’s embrace of the concept of worker cooperatives provides a window into a body of social thought that one day we may be glad that we preserved.

“Father, do not say you have nothing to live for. You have a great deal to live for. Live for humanity.”

This is what Leland Stanford heard his dying son tell him in a dream while he slept by the boy’s bedside, awakening to find his son had died.

Stanford quoted this dream as the event that gave birth to the idea of Leland Stanford, Junior, University, the memorial to his son. One can only speculate on what internal transformation may have occurred within Leland Stanford at the death of his only child. Other historical figures have also undergone profound transformations after personal tragedy. No documentation of Leland Stanford’s inner life appears to remain to resolve such speculation. Regardless of what we may imagine happened to Stanford the man, the historical record shows that in the years after this pivotal event, the Populist vision of worker-owned industry emerged as the recurring theme of Leland Stanford’s public endeavors. As a United States Senator (1885-1893), a large part of Stanford’s legislative efforts were toward bills that would give worker cooperatives the necessary legal structure and sources of credit in order to flourish. His advocacy of worker ownership was a prominent part of his newspaper interviews and his oratory in the Senate. In founding Leland Stanford Junior University, he made the cooperative vision “a leading feature lying at the foundation of the University,”

and he repeatedly reiterated this goal in his addresses to the Trustees, the students, and in the legal documents founding the University.

Could Stanford’s efforts have succeeded? Given that they were part of a social movement that in hindsight we know did not prevail, how indeed could they have? Stanford’s bills never made it out of committee, and his vision for Stanford University was not only left unrealized, but has been entirely

forgotten from the University’s

collective memory.

So thorough is this forgetting that even during the recent celebrations of the University’s

Centennial, there was not the slightest mention of Stanford’s cooperative vision in his founding goals for the University.

This historical anomaly presents a number of unanswered questions: Why was this component

of Stanford University’s charter never implemented? How did this aspect

of the University’s heritage become erased from its memory? And perhaps

most interesting, how did Leland Stanford, the great railroad “Robber

Baron”, the wealthiest man in the U.S. Senate, come to believe and advocate

that the corporate system of American industry should be replaced by a

cooperative system? This article explores what material remains that can answer these questions. I focus on Leland Stanford’s own words, and will attempt to bring the reader into the debate of that time, a debate whose resolution is the society we now live in.

STANFORD’S VISION OF COOPERATIVES

The vision of direct worker ownership of industry was, from the onset

of the Industrial Revolution, one of the solutions that labor activists

considered for ending the corporate exploitation of labor and its growing

domination of society.

Today’s ubiquitous calls for “more jobs” in every political campaign give no inkling that 100 years ago the entire concept of a “job” was still novel—and contested. A small window into that contest is provided by Charles Nordhoff, writing in 1875; we discover that the term “employee” had only recently gained usage as a euphemism to replace the less genteel “wage laborer”:

Though it is probable that for a long time to come the mass of mankind in civilized countries will find it both necessary and advantageous to labor for wages, and to accept the condition of hired laborers (or, as it has absurdly become the fashion to say, employees), every thoughtful and kind-hearted person must regard with interest any device or plan which promises to enable at least the more intelligent, enterprising, and determined part of those who are not capitalists to become such, and to cease to labor for hire.

Ten years later, the Populist vision of the cooperative commonwealth—of laborers owning their own factories and consumers owning their own stores—had grown to be the foundation of a democratic

mass movement.

Stanford’s advocacy of the cooperative vision began at least by 1885, when we find in the Grant of Endowment of Stanford University that the University shall teach “the right and advantages of association and co-operation”. In 1886 Stanford introduced a bill in to the U.S. Senate to foster the creation of worker co-ops, and in an 1887 interview about the bill, Stanford attested that his interest in worker cooperatives was part of his earliest thinking:

The great advantage to labor arising out of co-operative effort has been

apparent to me for many years. From my earliest acquaintance with the

science of political economy, it has been evident to my mind that capital

was the product of labor, and that therefore, in its best analysis there

could be no natural conflict between capital and labor, because there

could be no antagonism between cause and effect—between effort

and the result of effort; and, since capital is the product of labor, there could be no conflict between labor and its product. Keeping this fundamental principle in

view, it is obvious that the seeming antagonism between capital and labor

is the result of deceptive appearance. I have always been fully persuaded

that, through co-operation, labor could become its own employer.

At the root of Leland Stanford’s interest in worker cooperatives may have been a core experience going back thirty-five years, to his days with the Argonauts in the California gold rush.

In 1852, just a few years after gold was discovered in California, the 28 year old Leland Stanford decided to join his brothers in Gold Country. His wife Jane’s parents insisted that she remain home in Albany, New York, so Leland headed off alone. He spent three years with his brothers in Eldorado County running a hardware

business for the gold miners. The anarchy of the gold rush had produced a self-organized system of informal miner cooperatives. It was with these miners that Stanford saw cooperation

first-hand as an organizing force. In the newspaper interview Stanford continues with a description of this phenomenon. Stanford told the interviewer,

in a very alert and bright state of society

people learn co-operation by themselves, but in older and quieter conditions

of laboring enterprise, such a bill as I propose will point out the way

to mutual exertion. You may not remember that we flumed most of the streams

of California; a ditch was dug alongside of the river, and very often

a tunnel had to be made through rock to carry this water on, so that the

bed of the stream could be left dry and the gold taken out of it. Now,

all these flumes were made by co-operation, without there being any law.

Generally four or six men would unite to do this work; if there were

four, three of them worked at the tunnel and flumes, while the fourth

went off to a distance and got wages, so that he could supply them with

food. In that way the workers were kept alive by one man’s wages, and

he, in his turn, got his proportion of all gold taken out of the bed of

the stream.

“That must have been a high condition of society,” the interviewer said,

“for mere laborers?”

“Oh, yes,” replied Stanford,

I do not think there ever will be any thing

like it again. There were several hundred thousand young men finding

out for themselves the way to conquer nature and fortune; their systems

of doing things, derived from necessity and aided by their intelligence,

were the highest manifestations of self-government ever made in so short

a time.

Stanford was witness to an alternative social reality profoundly different from what he had seen in his life up to then, and he was astute enough to realize its implications. It permanently altered his horizon as to what was possible among human beings.

In this story we find a confirming example for the social-historical thesis that it is the direct experience of cultural alternatives which creates “a new way of looking at

society” and provides the foundation for democratic social movements.

For Stanford, these experiences evidently remained private revelations for thirty years, until the Populist movement and Stanford’s position as United States Senator and University founder created the opportunity for their public expression.

Stanford pursued three main avenues to advance his vision of a society of cooperative industries,

the first being its incorporation into the purposes of Stanford University,

the second being several bills he introduced into the U.S. Senate, and

the third being his use of the media. In the quotations that follow,

we will see the panoply of what Stanford had to say to the U.S. Senate, the Stanford University Trustees, students, and University President David Starr Jordan, and to the general public through the press.

Stanford’s own words can serve to introduce the basic ideas of the cooperative

movement. In Hubert H. Bancroft’s biography of Stanford, we read Stanford’s explanation for the basic problem of the capitalist economy:

In a condition of society and under an industrial organization

which places labor completely at the mercy of capital, the accumulations

of capital will necessarily be rapid, and an unequal distribution of wealth

is at once to be observed. This tendency would be carried to the utmost

extreme, until eventually the largest accumulations of capital would not

only subordinate labor but would override smaller aggregations.

Stanford then describes his prescription for halting this aggregation

of capital:

The one remedy for this tendency, which to all appearances

has been ineradicable from the industrial system, is the cooperation and

intelligent direction of labor.

What I believe is, the time has

come when the laboring men can perform for themselves the office of becoming

their own employers; that the employer class is less indispensable in

the modern organization of industries because the laboring men themselves

possess sufficient intelligence to organize into co-operative relation

and enjoy the entire benefits of their own labor. Whenever labor is sufficiently intelligent to do this, it should not wait patiently for it own employment by capital and enterprise, because whoever is competent to furnish himself employment, and therefore receive the full result of his own effort and hires out his time, is thereby rendering a voluntary servitude to capital, and every man possessed of industrial capacity is in possession of capital, for it is out of that industrial capacity that capital Is sustained in activity.

With a greater

intelligence, and with a better understanding of the principles of cooperation,

the adoption of them in practice will, in time I imagine, cause most of

the industries of the country to be carried on by these cooperative associations.

Stanford pointed to some concrete examples in interviews in the New York

Tribune and Cincinnati Enquirer in 1887:

A co-operative association

designed to furnish labor for farming operations is clearly within the

realm of practical achievement.

He countenanced workers taking over

his own line of work, the railroad:

A co-operative association of men

who know how to build a railroad might be able to take a contract just

as well as a corporation.

There is no undertaking open to capital,

however great the amount involved, that is not accessible to a certain

amount of labor voluntarily associated and intelligently directing its

own effort.

In 1886 Stanford authored a Senate bill to foster the creation of worker

cooperatives by providing a legal structure for incorporation. Stanford

told his fellow Senators when speaking on behalf of the bill,

The principle of co-operation of individuals is a most democratic one. It enables the requisite combination of numbers and capital to engage in and develop every enterprise of promise, however large. It is the absolute protection of the people against the possible monopoly of the few, and renders offensive monopoly, and a burdensome one, impossible.

Stanford’s analysis of the basic “principle of cooperation” is interesting

because it conceptualizes employment as a service that the worker pays

for, in the form of profits kept by the employer, and that providing this

service for themselves is the key to workers being able to keep the profits

of their labor. Stanford explained in his New York Tribune interview

that

voluntary association of labor into co-operative relation secures

to itself both the wages and the premium which, under the other form of

industrial organization would be paid to the enterprise directing it and

to the capital giving it employment. Capital appears to have an ascendancy

over labor, and so long as our industries are organized upon the divisions

of employer and employee, so long will capital retain that relation, but

associated labor would at once become its own master.

Stanford even developed a macroeconomic analysis on the effect that cooperatives

would have on the labor market and unemployment. Stanford continued,

When you see a man without employment ... the contemplation is necessarily saddening. The fault is with the organization of our industrial systems. The individual so circumstanced belongs to the class of people who wait the action of an employer, instead of originating employments for themselves. Now, the employer class originates employments only for the gratification of its own wants. The hirer of labor uses other men in the employed relation only to the extent that his own wants demand. Those, therefore, who having productive capacity, remain in poverty belong to the class who constitute the surplus over and above the numbers required to satisfy by the product of their labor the wants of the employer class. The numbers belonging to this surplus class would be constantly diminished, and would eventually disappear under the operation of the co-operative principle.

Stanford outlined three ways labor would be benefited:

- corporations

would have to increase wages to compete with cooperatives in hiring labor;

-

greater worker prosperity would translate into greater aggregate consumer

demand and hence more demand for labor; and

-

workers’experience

in self-management would flood the market with people able to organize

businesses and thus lower the comparative advantage of the employer class.

Regarding the effect on wages, Stanford said,

take, for instance, the influence

of co-operation upon the rate of wages to the employed class. In a co-operative

association conducting a business, and dividing the entire proceeds of

the business, the dividends so created would exceed the ordinary rate

of wages. The best mechanics and the best laborers would, therefore,

seek to acquire a position in a co-operative association. The reward

of labor being greater by co-operation, the employer would have to offer

additional inducement to labor to remain in its employ, because the superior

attractiveness of the co-operative plan would incite them to form societies

of this character, and employ their own labor. It would, therefore, have

a direct tendency to raise the rate of wages for all labor or in other

words, to narrow the margin between the amount paid for labor and its

gross product.

Regarding the effect on aggregate demand, Stanford said,

co-operation would so improve

the condition of the working men engaged in it that their own wants would

be multiplied, and a greater demand for labor would ensue.

And regarding the effect on competition within the employer class, Stanford explained,

Each co-operative

institution will, therefore, become a school of business in which each

member will acquire a knowledge of the laws of trade and commerce.

Co-operation would be a preparatory school qualifying men, not only to

direct their own energies, but to direct the labor and skill of others.

... With the increase in the number of employers there is necessarily

a corresponding intensity of competition between them in the field of

originating employment. This competitive relation alone would raise the

reward of labor. ... Thus co-operation will increase the number of those

qualified to originate employments, and thus import into the industrial

system a competition among the employer class, a condition highly favorable

to the employed.

Stanford understood the other major principle of cooperation, that the

cooperative would not only secure the profits for the workers, but would

change their basic relation to one another and to management:

The employee

is regarded by the employer merely in the light of his value as an operative.

His productive capacity alone is taken into account. His character for

honesty, truthfulness, good moral habits, are disregarded unless they

interfere with the extent and quality of his services. But when men are

about to enter partnership in the way of co-operation, the whole range

of character comes under careful scrutiny. Each individual member of

a co-operative society being the employer of his own labor, works with

that interest which is inseparable from the new position he enjoys. Each

has an interest in the other; each is interested in the other’s health,

in his sobriety, in his intelligence, in his general competency, and each

is a guard upon the other’s conduct. There would be no idling in a co-operative

workshop. Each workman being an employer, has a spur to his own industry,

and also has a pecuniary reason for being watchful of the industry of

his fellow workmen.

Stanford’s analysis is mirrored in recent studies

of productivity in worker cooperatives.

In concluding his lengthy New York Tribune interview, Stanford drove home

his vision by imagining what would happen if the industrial system had

always been cooperative, and now someone were proposing to reorganize

it as a corporate system:

To comprehend it in all its breadth, however, let us assume that in all

time all labor had been thus self directing. If instead of the proposition

before us to change the industrial system from the employed relation and

place it under self direction, the co-operative form of industrial organization

had existed from all time, and we were now for the first time proposing

to reorganize the employment of labor, and place it under non-concurrent

direction, I apprehend the proposer of such a change would be regarded

in the light of an enslaver of his race. He would be amenable to the

charge that his effort was in the direction of reducing the laboring man

to an automaton, and that vague apprehension with which

all untried experiments are beset would leave but small distinction in the minds

of workingmen between the submission of all labor to the uncontrolled

direction of an employer, and actual slavery.

We may safely assume that such a change would be impossible—that men

are not likely to voluntarily surrender the independence of character

which co-operation would establish for any lower degree of servitude ... . In fact co-operation is merely an extension to the industrial life

of our people of our great political system of self-government. That

government itself is founded upon the great doctrine of the consent of

the governed, and has its corner stone in the memorable principle that

men are endowed with inalienable rights. This great principle has a clearly

defined place in cooperative organization. The right of each individual

in any relation to secure to himself the full benefits of his intelligence,

his capacity, his industry and skill are among the inalienable inheritances

of humanity.

One may wonder, given these views about capitalism, what Stanford thought

about his own career and those of his fellow industrialists. He saw employers

as having been necessary in the development of industry up to that point,

but ultimately a role to be dispensed with. In his 1887 New York Tribune interview, Stanford reiterates five times that “the employer of labor is a benefactor.”

The employers of labor are the greatest benefactors to mankind.

They promote industry; they foster a spirit

of enterprise; they conceive all the great

plans to which the possibilities of civilization

invite them; and the association of

laboring men into co-operative relation,

which in a large measure can take the

place of the employer class, must therefore

of necessity be enobling.

In the biography by Bancroft, Stanford explains,

Those who by their enterprise furnish employment for others

perform a very great and indispensable office in our systems of industry,

as now organized, but self-employment should be the aim of every

one.

In American usage today, the terms capitalism and free enterprise are

used so interchangeably that the idea of a free enterprise system distinct

from capitalism sounds self-contradictory. Furthermore, capitalist and

communist ideologies both posit corporate versus state ownership as the

inherent opposites between which we are to choose. But clearly, Stanford

was advocating a “third way”—direct worker ownership which he saw as

the ultimate and most enlightened form of free enterprise.

The voluntary nature of this alternative was central to Stanford’s viewpoint,

and he was highly critical of coercive or governmental redistribution

of wealth, which was advocated by communist and other movements of the

time. The inalienable rights of the citizen were paramount to Stanford;

he pointed to the principles in the Declaration of Independence as being

essential for just government, and that

with these principles fully recognized, agrarianism and communism can have only an ephemeral existence. ... [Cooperatives] will accomplish all that is sought to be secured by the labor leagues,

trades-unions and other federations of workmen, and will be free from

the objection of even impliedly attempting to take the unauthorized or

wrongful control of the property, capital or time of others.

Stanford elaborated:

The political economists and the communists have much to say concerning the distribution of wealth. ... Many writers upon the science of political economy

have declared that it is the duty of a nation first to encourage the creation

of wealth; and second, to direct and control its distribution. All such

theories are delusive. The production of wealth is the result of agreement

between labor and capital, between employer and employed. Its distribution,

therefore, will follow the law of its creation, or great injustice will

be done. ... The only distribution of wealth which is the product of labor,

which will be honest, will come through a more equal distribution of the

productive capacity of men, and the co-operative principle leads directly

to this consummation. All legislative experiments in the way of making

forcible distribution of the wealth produced in any country have failed.

Their first effect has been to destroy wealth, to destroy productive industries,

to paralyze enterprise, and to inflict upon labor the greatest calamities

it has ever encountered.

Stanford took pains during the discussion of his views to counter the

idea that labor and capital were inherently opposed. “The real conflict,

if any exists,” Stanford explained, “is between two industrial systems.”

He goes on to illustrate thus:

The country blacksmith who employs no journeyman is never conscious of

any conflict between the capital invested in his anvil, hammer and bellows,

and the labor he performs with them, because in fact, there is none.

If he takes a partner, and the two join their labor into co-operative

relation, there is still no point at which a conflict may arise between

the money invested in the tools and the labor which is performed with

them; and if, further in pursuance of the principal of co-operation,

he takes in five or six partners, there is still complete absence of all

conflict between labor and capital. But if he, being a single proprietor,

employs three or four journeymen, and out of the product of their labor

pays them wages, and, as a reward for giving them employment and directing

their labor, retains to himself the premium, ... the line of difference

between the wages and the premium may become a disputed one; but it should

be clearly perceived that the dispute is not between capital and labor,

but between the partial and actual realization of co-operation.

Thus, to Stanford, those who believed that class struggle was inescapable

had failed to understand the alternative of worker cooperation, which

he believed would prevail as the highest state of industrial organization:

As intelligence has increased and been more widely diffused among men,

greater discontent has been observable, and men say the conflict between

capital and labor is intensifying, when the real truth is, that by the

increase of intelligence men are becoming more nearly capable of co-operation.

Again referring to profits as the “premium” paid to capital, Stanford

concluded,

In a still higher state of intelligence this premium will

be eliminated altogether, because labor can and will become its own employer

through co-operative association.

WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Leland Stanford has always been acknowledged for the strong support he gave to the cause of women’s rights. He supported suffrage, women’s participation in politics, equal pay for equal work,

and equal educational opportunities. In founding the University he required for the Trustees “To afford equal facilities and give equal advantages in the University to both sexes”.

Some historians have depicted Stanford’s goal in having women attend the University as being solely to prepare them to be “better mothers”. When Stanford writes about his coeducational goals for the University, his words are ambiguous as to his ideas about inherent gender roles for women. Stanford told the Trustees in his first meeting with them:

We deem it of the first importance that the education of both sexes shall be equally full and complete, varied only as nature dictates. The rights of one sex, political and otherwise, are the same as those of the other sex, and this equality of rights ought to be fully recognized.

In the last letter Stanford wrote before he died, to University President David Starr Jordan, he reiterated his coeducational goals, telling Jordan,

I want, in this school, that one sex shall have equal advantage with the other, and I want particularly that females shall have open to them every employment suitable to their sex.

From these words alone we cannot conclude whether Stanford’s concept of equality for women was narrow or wide. At this time there were widely divergent views as to what “nature dictated” for women, or left “suitable to their sex”. One is tempted to draw conclusions from the fact that Stanford chose no women as University Trustees, despite his stated goals for coeducation at the University.

However, a clearer picture of Stanford’s views emerges in an 1887 interview Stanford gave to the Cincinnati Enquirer regarding his bill before the U.S. Senate to promote the creation of worker cooperatives. In the interview, Stanford took the opportunity to confront the stereotype that women were emotionally unsuited for political power. The reporter interviewing Stanford remarked that “the subject of female suffrage seemed to be incidental to this subject.” Stanford replied:

I am in favor of carrying out the Declaration of Independence to women as well as men. Women having to suffer the burdens of society and government should have their equal rights in it. They do not receive their rights in full proportion.

The reporter said, “But they have very much advanced; for a good many years they have been Government clerks, and now they are becoming postmasters and school directors.”

“Yes,” replied Stanford sardonically,

they are employed here in the public departments at just one-half the pay men receive for doing the same work. What is the reason for that? A very intelligent lady said to me yesterday that she thought women were not for politics, and that there were but few things women could do. I remarked that I never saw a woman to come into one of our mining camps in California but her mere presence effected a change in the conduct of all the men there. It would be the same in the suffrage; instead of there being more riot and bad behavior when women appear there will be better conduct and more respect for the law.

Said the reporter: “Do you not think women will go off on sentimental issues if they undertake the business of government and break up the organizations by which men work out large ends?”

“Oh!” said Stanford,

it is not sentiment that we have to fear so much as we suppose. A man’s sentiments are generally just and right, while it is second selfish thought which makes him trim and adopt some other view. The best reforms are worked out when sentiment operates, as it does in women, with the indignation of righteousness.

Other writings show that Stanford did not see any limitations on women’s roles in business beyond what could be accommodated by a maternity leave. Stanford emphasized that the constraints that women found in the workplace were not due to their own limitations, but rather to the failure of their workplaces to take into account their needs. And the cause of this failure of the workplace, Stanford articulated, was its lack of democracy, a cause that could be remedied by worker cooperatives.

In Stanford’s advocacy of worker cooperatives he repeatedly pointed to their

benefits for women because of the cooperative’s intrinsically democratic

nature. Stanford described four ways the cooperative would benefit women:

- by giving women new access to job opportunities,

- by allowing women to participate in running the business at all levels,

- by offering protection from exploitation, and

- by fostering working conditions based on women’s needs.

Stanford told the U.S. Senate when he introduced his co-op bill,

One of the difficulties in the employment of women arises from their domestic

duties; but co-operation would provide for a general utilization of their

capacities and permit the prosecution of their business, without harm,

because of the temporary incapacity of the individual to prosecute her

calling. And if this co-operation shall relieve them of the temporary

incapacity arising from the duties incident to motherhood, then their

capacity for production may be utilized to the greatest extent. Very

many of the industries would be open to and managed as well by women in

their co-operative capacity as by men.

As an example of how cooperatives would remove the exploitation of women,

Stanford said,

There is no reason why the women of the country should

not greatly advance themselves by this act. Take the matter of clothing

alone; there are sixty million people in America, and if each expends

$10 a year for clothes, that makes $600 million; it might just as well

go to co-operative associations of women as to these large partnerships

which pay hardly living wages. At the same time the grade of woman’s

labor would be advanced; they would become cutters, style-makers, &c.

Regarding the particular needs of working women due to maternity, Stanford

pointed out that since each cooperative is organized to meet its members’

needs, “under co-operation they would draw wages when they could not labor,

or the character of the labor could be changed for them.”

Stanford

was saying, in effect, that cooperatives are structured to produce humane

responses, as a matter of course, to needs such as maternity. The enduring

difficulty that business has had in responding to such issues is evident

in the current controversies over childcare, the corporate “mommy track”,

and attempted solutions such as “flextime”.

In his comments on women’s rights, Stanford again approaches the issue not by recommending that the current power holders should change their policies, but by recommending a democratic structuring of the workplace—and the body politic—will tend, of its own accord, to produce more just and humane policies.

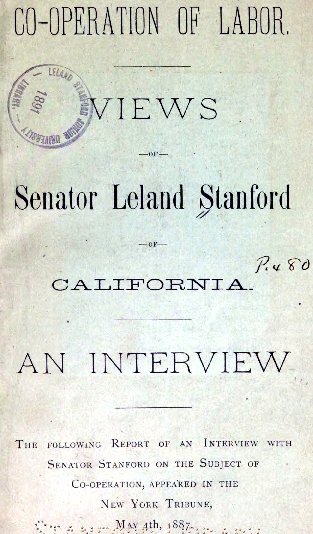

IN THE SENATE

Stanford authored several bills in the U.S. Senate to help implement his

cooperative vision. The first was his bill to provide a legal basis for the incorporation of worker cooperatives in the District of Columbia, to serve as a template for the rest of the nation. On May 4, 1887 he was interviewed in the New York Tribune about his bill, where he described that part of the bill’s purpose was to

attract attention to the value of the co-operative

principle upon which our industrial systems should be founded. It will

be a governmental attestation to the value of the co-operative principle,

which alone can eliminate what has been called the conflict between capital

and labor.

This interview appeared, perhaps by no coincidence, on the first anniversary

of the Haymarket Riot in Chicago. This was both fitting and ironic.

The Haymarket riot erupted during a massive strike for the eight-hour

day by 200,000 workers and turned into one of the bloodiest attacks on

labor demonstrators in U.S. history. It brought labor issues to forefront,

but also proved to be the beginning of the end for the Knights of Labor,

and with it, the centrality of worker cooperatives for the US labor movement.

His writing of the co-op bill appears to have been the closest that Stanford got

to actually forming a cooperative, so it is instructive to examine the

text. Most significant is that voting rights within the cooperative were

to be based on the amount of capital contributed by each member, rather

than one person, one vote. Governance based on one-person, one-vote, rather than capital contributions, was an essential plank of the theory of cooperatives as articulated in the the “Rochdale Principles” developed in England.

Stanford gives no evidence of having been aware of the Rochdale Principles nor of the reasoning behind them, which would support the conclusion that despite his advocacy of worker cooperatives,

he was distant from the grassroots cooperative movement itself.

Yet Stanford was aware of the necessity for a mass political movement

in order to achieve social change. To his Senate colleagues he declared,

In the unrest of the masses I augur great good. It is by their realizing

that their condition of life is not what it ought to be that vast improvements

may be accomplished.

Stanford seems to have followed the movement closely enough to put some

of its basic ideas into legislation, and his most famous effort was his

bill for issuing currency based on agricultural land value. In the late

1880s many of the huge farmers’cooperatives failed in large part because the banking establishment refused to finance them. It was the problem of access to capital, and the control of the currency by the banking establishment, that drove the cooperatives into the political arena with the founding of the People’s Party.

A central plank of the People’s Party was the “subtreasury” system unveiled

at the Populist convention in St. Louis in December 1889.

Farmers would be able to draw money by depositing their products in subtreasuries of the U.S. Treasury, and be able to sell their goods when the market price was highest. Three months after the subtreasury plan was declared, Leland Stanford authored his own even more ambitious plan to lend money to farmers not on the basis of their crop value, but upon their land value. By injecting money into the economy directly through the farmers, credit would become so readily obtained that cooperatives should flourish, as well as small and large industry generally.

Stanford told the Senate during one of his several speeches on behalf

of the bill,

Legislation has been and is still directed towards the protection

of wealth, rather than towards the far more important interests of labor

on which everything of value to mankind depends. ... When money is controlled

by a few it gives that few an undue power and control over labor and the

resources of the country. Labor will have its best return when the laborer

can control its disposal; with an abundance of money, and through co-operation, this end will be practically attained.

In his fifth speech on the subject of money supply, the last time he addressed the Senate, Stanford said,

To a great extent [a sufficiency of money] means to the

laborer emancipation through his ability to be his own employer. With

an abundance of money unskilled laborers, mechanics, and other workingmen

will be able to carry on co-operative societies, because they will be

able to obtain the credit they deserve, and even if employed by capital

all cause for dissension between employed and employer will be removed,

as co-operation will regulate the price of labor and be its perfect defense

against inadequate compensation. ... Money is the great tool through whose

means labor and skill become universally co-operative ... .

This bill was widely discussed, earning Stanford, the wealthiest man in

the Senate, criticism as being “fully impregnated with socialistic ideas”,

and spawning moves by some within the Farmers’Alliance and People’s Party

to nominate Stanford as their candidate for President in the 1892 election

(a move that Stanford declined).

Reactions to Stanford's bill appeared in newspapers throughout the country.

The Washington Post reported on March 10, 1890, that “Senator Stanford has received a number of telegrams from bankers and others criticizing the resolution, and declaring that if the scheme he proposes should become a law it will virtually destroy the banking business of the country.”

The Women's Chronicle out of Little Rock, Arkansas, on March 29, 1890, wrote

The senator has discovered that something is

wrong with some of the branches of prosperity

in our country, and straightway,

with the unerring instinct of natural wisdom,

he proposes to doctor the root.

Good for Senator Stanford.

J. E. Hatch of West Eaton, N. Y., wrote in an April 2, 1890 letter to the Editor of The National View (the Greenback Party newspaper), “Senator Stanford's scheme, if adopted, will not only relieve the financial depression, but will make him president.”

An editorial opposing Stanford in the New York Sun stated,

Senator Stanford, of California is hardly the man from whom an outburst

of socialism and sentimental political

economy would be expected, but the resolution

offered by him on Monday is such an outburst.

...

The fostering care of the government exerted in the direction proposed by the California senator would soon bring about a pretty condition of things. All the thriftless or reckless farmers would borrow money of the government. All the wornout and worthless land now in private hands would be unloaded upon the government. The first step, and a very long step, in the “nationalization” of the land would have been taken.

The Political Record of San Francisco accused Stanford of Machiavellian subterfuge:

Did Stanford mean it? Well yes—to talk

about till the railroad debt bill was passed,

2 per cent, for seventy five years. It was

to make that bill look reasonable. It

was to cover up that steal. It was to

get friends for that project, only that and

nothing more.

...

He is false as hell, and this proposition

shows it. He knows it would be wreck,

ruin, speculation, extravagance, collapse,

and general agony for all. Our land is

worth at at least $10,000,000,000. Every

owner would draw paper, all he could, at

2 per cent, to loan out at 3, 4, 5. Ten

thousand wild-cat schemes would jump into

being. Legitimate productive business

would be abandoned for grand enterprise.

And then the collapse. ...

In support of Stanford, Our Own Opinion of Hastings, Nebraska, wrote:

It is in order now, to misrepresent, ridicule

and abuse Senator Stanford, of California.

He has in the eyes of the money

god, committed the unpardonable sin.

The national banks will let loose their

blood hounds, to terrify the brave senator,

who has dared present a bill in the

interest of a suffering people. A bill

which asks the government to lend its

credit to the people, on unquestionable

security, at the same easy terms, it has

accorded to over 3000 national banks.

The Iowa Tribune wrote on April 12, 1890,

SENATOR STANFORD knows what the people

need, cheap and abundant money, but

his millionaire brothers will be applying

to get rooms for him in some fashionable

insane asylum.

... We suggest

that the readers of this paper invest a

postal card apiece. Tell Senator Stanford

over your own name that he has introduced

the most important proposition

into the United States senate that was

ever made there, a proposition to free a

race from bondage. Ask him to crowd

it to a vote, and never to let up until success

crowns his efforts. Do not put it off a day. The bankers have telegraphed him long messages to tell him of the ruin

to their skinflint business which would

result. Let the people write him of the

general prosperity which would follow

United State loans upon farms.

One last example provided here is from The Industrial Union, Columbus, Ohio, from May 3, 1890:

Senator Stanford's proposition is the

most patriotic and far reaching scheme to

liberate the industrial world from piratical extortioners that has ever been offered,

but as to its potency is the fact that it

comes from a man whose relations to

business are, one might suppose,

to be with the plutocratic, whose

opposition and criticisms he directly invites. ... In Senator

Stanford's interview, published in the

Argonaut, San Francisco, Cal., recently,

he has burned all the bridges in his rear

and return is impossible.

...

Every man and woman in the United States should become champions of Senator Stanford and his joint resolution now before the senate. It means better times, better prices relief from debt, the freedom from extortion, the encouragement of production, the employment of labor, the breathing relay station of this era and the centuries that are to come. Organize Stanford clubs for this reformation and wait not a moment.

Stanford paid a personal price for his efforts in the Senate: it cost him his position as president of the Southern Pacific Railroad. Stanford’s business partner Collis Huntington had been angry about Stanford’s political ambitions, and felt

Stanford had neglected the railroad since being elected to the Senate.

But according to the story emerging from the inner circle of the railroad

associates (reported in the San Francisco Chronicle), it was Stanford’s

land loan bill “that finally precipitated a declaration of war” which

resulted in Stanford’s ouster.

A possible indication of the lasting impression that Stanford’s efforts

left on organized labor was an incident that occurred during the great

Pullman railroad strike a year after Stanford’s death. Jane Stanford

was up in Dunsmuir, California, and urgently needed to get back to San

Francisco. A California committee of the American Railway Union, which

called the strike, went so far as to make up a special train to transport

her, out of their respect for Leland Stanford’s memory.

ON THE FARM

“I want this institution to deal particularly with the welfare of the

masses,” wrote Stanford to University President Jordan, in the last signed

letter he ever wrote.

The few very rich can get their education anywhere. They will

be welcome to this institution if they come, but the object is more particularly

to reach the multitude—those people who have to consider the expenditure

of every dollar.

|

Leland Stanford believed in the Enlightenment thesis that new ideas had the power

to improve the society, and did not subscribe to the view that social change was purely an

outcome of “class struggle”. Stanford’s approach to “the welfare of the masses”

was not moralistic, but technical. He blamed neither employee or employer

for inequalities in wealth, but rather, the advantage of the capitalist

class over the non-capitalist class in its power to organize business

enterprises, and this Stanford saw as fundamentally a matter of education.

Thus he placed his other main effort to promote cooperatives into education,

and in particular, into Stanford University.

Stanford gave a lengthy exposition of his purposes for the University to his biographer, Hubert H. Bancroft. After describing two foundational purposes of the University—first, “to

mould in the mind of its students an inseparable union in the evolution

of theoretical and practical knowledge” and “to teach the law of success in every calling,” and second, “to make the university a conservator of right theories of government”, he arrives at his third purpose, to help bring about the worker ownership of industry:

Third, and in general, a leading feature lying at the foundation

of the university relates to the cooperation of labor. The wealth-producing

power of each individual is discounted when he labors for

another. Those who by their enterprise furnish employment for others

perform a very great and indispensable office in our systems of industry,

as now organized, but self-employment should be the aim of every

one. No mind, however fertile in resource, or however imbued with

benevolent thought, can devise a system more replete with promise

of good to men than the cooperation into effective relation of the labor

of those who work with their hands. This cooperative principle as

applied to capital has been signally successful wherever it has been

been adopted.

The labor of a

single individual possesses but a small part of the wealth-producing

capacity which would inure to it if it were associated with the labor

of a hundred individuals into cooperative relation under intelligent

direction.

There is no undertaking, however great, which may not be undertaken

if labor sufficient for its accomplishment is brought into cooperative

relation, particularly if that relation be actively organized

and under wise and judicious direction. Capital being the product of

labor, I think I have already said the aggregation of labor is the

exact equivalent of capital.

To a superficial consideration

of the subject, capital seems to possess an advantage over labor; but

the conclusions from such superficial observation are erroneous. Produce

in the minds of the laboring classes the same facility for combining their

labor that exists in the minds of capitalists, and labor would become

entirely independent of faculty. It would sustain to capital a relation

of perfect independence.

That this remedy has not been seized upon and adopted by the masses of

laboring men is due wholly to the inadequacy of educational systems.

Great social principles and social forces are availed of by men only after

an intelligent perception of their value. It will be the aim of the university

to educate those who come within its atmosphere in the direction of cooperation.

Many experiments in this direction have been made, and whatever of failure

has attended them has been due to imperfection of educated faculties.

Stanford recognized that the individual development of the student would

also be an important factor in the making of the cooperative workplace.

Thus he continued his exposition:

The operation of the cooperative principle

in the performance of the labor of the world requires an educated perception

of its value, the special formation of character adapted to such new relation,

and the acquirement of that degree of intelligence which confers upon

individual character and adaptability to this relation. It will be the

leading aim of the university to form the character and the perception

of its industrial students into that fitness wherein associated effort

will be the natural and pleasurable result of their industrial career.

Stanford’s thinking anticipated recent studies on the importance

of experiential preparation for the cooperative workplace.

Stanford put his goals for the University in perspective with his summary:

We have then the three great leading objects of the university:

- first, education,

with the object of enhancing the productive capacity of men equally with

their intellectual culture;

- second, the conservation of the great doctrines

of inalienable right in the citizen as the cornerstone of just government;

- third, the independence of capital and the self-employment of non-capitalist

classes, by such system of instruction as will tend to the establishment

of cooperative effort in the industrial systems of the future. ... these distinctive objects, imperfectly presented here, constitute

perhaps the most striking features of distinctiveness which will

be characteristic of this university.

Stanford’s exposition makes it quite clear that his cooperative vision was in no way tangential or incidental to his plans for Stanford University. It lay at the very core of what he was trying to accomplish in founding the University.

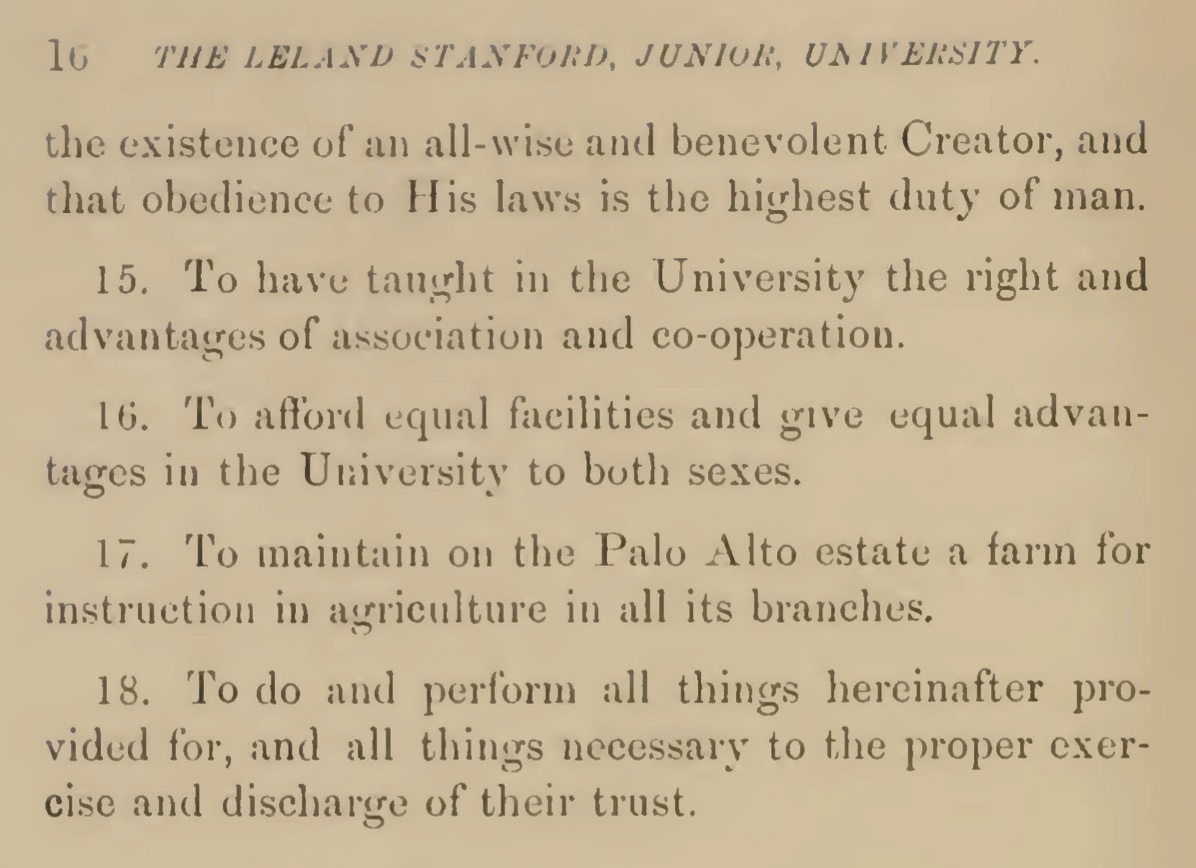

To ensure that his aims for the University would be met, Stanford placed

in the Grant of Endowment the clause that the Trustees

shall have the

power, and it shall be their duty ... To have taught in the University

the right and advantages of association and co-operation.

(There were

also three other clauses of topical instruction to the Trustees, to insure

that non-sectarian religious instruction, agriculture

, and equal gender

rights each be included in the University.

)

When Stanford addressed the first meeting of the Trustees, on November

14, 1885, he told them:

Out of these suggestions grows the consideration

of the great advantages, especially to the laboring

man, of co-operation, by which each individual has

the benefit of the intellectual and physical forces of

his associates. It is by the intelligent application of

these principles that there will be found the greatest lever to elevate

the mass of humanity, and laws should be formed to protect and develop

co-operative associations. Laws with this object in view will furnish

to the poor man complete protection against the monopoly of the rich;

and such laws properly administered and availed of, will insure to the

workers of the country the full fruits of their industry and enterprise.

They will accomplish all that is sought to be

secured by the labor leagues, trades unions, and other

federations of workmen, and will be free from the

objection of attempting to take the unauthorized or

wrongful control of the property, capital, or time of

others. Hence it is that we have provided for thorough instruction in the

principles of co-operation. We would have it early instilled into the

student’s mind that no greater blow can be struck at labor than that which

makes its products insecure.

How did the public react to Stanford’s placing the cooperative vision

at the foundation of the University? One sample we find is a sermon on

the founding of Stanford University, delivered in November 1885 by Rev.

Horatio Stebbins (who was later appointed a University Trustee), at the

First Unitarian Church in San Francisco, in which he extolled Leland Stanford’s

cooperative vision:

In setting forth some principles of great social

import that shall be taught in the future University, Mr. Stanford has

touched the key-note of modern time. I refer to the principle of co-operation.

To this principle it appears to me the best minds are looking for the

solution of some of the most complex social and industrial problems. ...

That a distinguished American citizen, on whom has descended the prosperity

of an epoch in affairs, should incorporate it in the foundation of a great

school, charged to call to its aid the best minds in Christendom, is a

prophetic event of promise and hope in the history of our time.

At the Opening Exercises in 1891 Stanford told the first class of Stanford

students,

We have also provided that the benefits resulting from co-operation

shall be freely taught. It is through co-operation that modern progress has been mostly achieved. Co-operative societies bring forth the best

capacities, the best influences of the individual for the benefit of the

whole, while the good influences of the many aid the individual.

Some of these students apparently took Stanford’s words to heart and founded

the Leland Stanford Junior University Cooperative Association (a.k.a. Students Cooperative Association) in 1891, which operated the first campus bookstore for seven years, supplanted by the faculty-owned cooperative Stanford Bookstore, which exists to this day. The members of the Board of Directors of the Co-op included several who would go on

to become leading actors in the University. Among them was freshman George

Crothers, future University Trustee and legal-eagle, for whom Crothers

Hall is named, graduate student Carl Lane Clemans, who founded

the Stanford Sigma Nu fraternity and built the first student-owned residence on campus, and was the winning half-back in the first “Big Game”, and Professor Charles David “Daddy” Marx, for whom Marx

Hall is named.

Marx also served as president of the Board of Trustees

of Palo Alto High School, which began as a parent-run cooperative.

In 1892, sophomore and future United States President Herbert Hoover co-founded the University's first student housing cooperative, Romero Hall, on Waverley Street, for the same reason that the University Students Cooperative Association would be founded in Berkeley 40 years later — to make college affordable. A number of the Board members of the co-op bookstore lived in Romero Hall.

The student newspaper, The Daily Palo Alto, ran a story in January 1893, “Senator Stanford's Views on Cooperation,” bringing attention to Stanford’s vision. It refers tellingly to “the side of the fence he is on”:

To all students who are interested in the practical affairs of life, it will be interesting to know the position Senator Stanford holds on the cooperative plan. The fact that he has introduced a bill to provide for co-operation in the District of Columbia tells very forcibly the side of the fence he is on. In his speech before the Senate he said that in a large sense civilization itself rests and advances on the great principles of co-operation; that the weak by its means are strengthened, and the one in least capacity is brought up in advantages to the level of the best, and the result brings all closer to the entire fruits of the united industries. He thinks that with greater intelligence and better understanding of its principles, the majority of the nation's industries will be thus carried on... We hope to give at an early date the Senator's views on his land loan bill.

In November, five months after Stanford had died, The Daily again published this excerpt from Stanford’s Senate speech.

A group of low income students took over the barracks that had housed

the University’s construction workers and ran it, in the description of

one writer, as a “self-managed democratic co-operative” known simply as

“The Camp”. Although the buildings were inhabited long after their intended

lifetime, Jane Stanford allowed The Camp to continue until 1902 because

she felt it embodied Leland Stanford’s social ideals.

What evidence do we find that “thorough instruction in the principles

of cooperation” was provided for? The course catalog for the first year

lists Economics 16, “Co-operation: Its History and Influence”, but no

such course is found in subsequent catalogs. What other evidence there

may be that bears on this question has yet to be discovered.

In Stanford’s last signed letter before his death, he wrote to University

President Jordan,

I think one of the most important things to be taught

in the institution is co-operation. ... By co-operation society has the

benefit of the best capacities, and where there is an organized co-operative

society the strongest and best capacity inures to the benefit of each.

It is enlightening to compare Stanford’s vision for the University with the visions for higher education that populate contemporary American debate. The benefits of education are never described in terms of changing how power is exercised within the society. Rather, education is relegated solely

to helping students gain an advantage in the job market, increasing

our “national competitiveness”, or canonizing a “common culture”. Stanford’s intention, on the other hand—that the laboring classes

be taught the principles of cooperation in order to gain ownership

of their workplaces—is of a radical nature wholly beyond the current

level of debate in the United States, from the right or from the left. This need not be seen so much as a reflection on Leland Stanford, but as a result of the depth of change that occurred in our society in the past 100 years.

DEFEAT

What became of Stanford’s efforts to advance worker cooperatives in the

Senate and at the University? Stanford was unable to get either his

co-op bill or his land loan bill passed in the Senate.

Stanford’s 1886

co-op bill was reported favorably to the Senate by the Judiciary Committee

but was dropped from the calendar because of Stanford’s absence due to

illness. He reintroduced it in 1891 but it again suffered the same fate.

Stanford’s land loan bill had a very different course. From the moment

he introduced it he met opposition in the Senate. But Stanford fought

tenaciously for this bill, and his motivation was not merely the immediate

effect which the bill would produce, but the greenback theory that “money

is entirely the creature of law” which was the basis of the bill.

In his fourth Senate speech on behalf of the bill Stanford reached his

pinnacle of oratory with quotations from John Law, James D. Holden, Aristotle,

Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, Benjamin Franklin, David Hume, and John Stuart

Mill. After his speech, the Populist Senator William Peffer from Kansas

stood up and gave an even lengthier speech on behalf of Stanford’s bill.

Stanford introduced the land loan bill three times between 1890 and 1892,

and each time it was killed by the Finance Committee. In 1892 he introduced

another bill for the free coining of silver, and his speech in its behalf on March 30, 1892 was his last in the Senate. This bill, too, was killed by the Finance Committee.

The Senate was not yet ready for the “revolution in finance” that Stanford was offering.

McKinley would win

the 1896 Presidential election campaigning against just such financial

revolutions.

At the University, Stanford’s vision of an education to support worker

cooperatives never became established. To a large degree, this might

be due to Stanford’s death two years after the University opened. David

Starr Jordan continued as University President while Jane Stanford took

on the governance of the University as the sole Trustee.

President Jordan did continue to speak of Stanford’s cooperative vision as late as 1915, in his essay, “Stanford’s Foundation Ideals”. Jordan devotes almost one page out of 13 to Stanford’s ideas about cooperatives, but he makes no mention of any obligation “to have taught in the University

the right and advantages of association and co-operation,” nor its implementation. I have found no evidence that Jane Stanford partook of Leland Stanford’s interest in worker cooperatives.

But the ultimate reason Leland Stanford’s vision was not implemented in the University probably goes beyond this. There are limits to what one

person, even one as influential as Leland Stanford, can do to change society in the absence of a mass movement. And with McKinley’s election and the defeat of the Populists in 1896, the cooperative movement was crushed.

Moreover, an answer can be sought in the structure of the University

itself. Leland Stanford had no apparent experience in actually setting

up cooperatives, and when he established the University, he gave it a

standard hierarchical corporate structure, with a sovereign Board of Trustees choosing a President with complete executive power. With Leland Stanford gone, and the movement gone, there was no longer any organic connection between the cooperative vision and the University. Stanford missed the opportunity to forge such a connection when he failed to establish the University itself under a cooperative model.

Leland Stanford’s vision was not only forgone, but over time was entirely forgotten by the Stanford University community. This forgetting appears to have been fairly rapid, occurring within the first decade of the University. Undoubtedly most of the faculty and administrators knew of Stanford’s wishes, but they ceased to speak and write of them, and thus the knowledge was not transmitted.

Stanford’s cooperative vision was independently rediscovered several times during the 1930s and ’40s, and thus new lineages for the knowledge were started. In c. 1939 a student cooperative house was organized, named after the late Professor of Political Science Walter Thompson, who was active in the cooperative movement that emerged during the Great Depression. President Tresidder’s administration terminated the co-op in 1945. In “an obituary” for the house in the August 23 Stanford Daily, student Cyclone Covey makes reference to Stanford’s cooperative vision for the University.

Such lore, one may conjecture, was passed down by Professor Thompson. Chemistry Professor J. Murray Luck, a founder of the Palo Alto Consumer Co-op, had also rediscovered Stanford’s writings on cooperatives, and shared that knowledge with the Palo Alto Co-op membership in 1950.

However, when student housing co-ops were started again

20 years later, no mention of Stanford’s vision can be found.

One

can conjecture that in the atmosphere of the McCarthy era, these lineages

of Stanford lore too became extinct.

Ultimately, the forgetting of Stanford’s vision cannot be explained by

the actions of anyone in particular, for the documentation of Leland Stanford’s

wishes regarding worker cooperatives has always been available to anyone

who cared to read it.

To account for the selective omission of Stanford’s

views from the campus memory

, I draw upon the analysis of the Lawrence

Goodwyn, an historian of the Populist era.

In describing “the triumph of the corporate state” which was completed

with the defeat of the Populists, Goodwyn writes,

A consensus thus came

to be silently ratified: reform politics need not concern itself with

structural alteration of the economic customs of the society. This conclusion,

of course, had the effect of removing from mainstream reform politics

the idea of people in an industrial society gaining significant degrees

of autonomy in the structure of their own lives. The reform tradition

of the twentieth century unconsciously defined itself within the framework

of inherited power relationships. The range of political possibility

was decisively narrowed not by repression, or exile, or guns, but by

the simple power of the reigning new culture itself.

“The ultimate victory”, Goodwyn continues, “is nailed into place, therefore,

only when the population has been persuaded to define all conceivable

political activity within the limits of existing custom.”

The cooperative vision, although it has survived in the refugia of cooperative

businesses in the U.S.,

has remained unavailable as a concept to most

Americans. Goodwyn could have been just as well addressing Stanford University’s

selective loss of its own history when he wrote:

Indeed, the remarkable

cultural hegemony prevailing militates against serious inquiry into the

underlying economic health of American society, so this information is,

first, not available, and second, its non-availability is not a subject

of public debate.

Consequently, Goodwyn concludes,

The ultimate cultural victory being

not merely to win an argument but to remove the subject from the agenda

of future contention, the consolidation of values that so successfully

submerged the ‘financial question’ beyond the purview of succeeding generations

was self-sustaining and largely invisible.

This article is written in the hope that perhaps now, during the centennial

of Stanford University, this central component of its founding vision

may become less invisible. I hope that this article may be taken as a

starting point for further historical study.

Epilogue

This article, published by the Stanford Historical Society, was the sole information printed during the centennial of Stanford University (1985-1991) that referred to Leland Stanford’s cooperative vision and its place in his mission for the University. Amid the voluminous material produced by the University itself (e.g. Birth of the University, News Release 05/13/91), none mentioned Leland Stanford’s advocacy of worker cooperatives, nor the actual stipulations that Stanford placed in the University’s Grant of Endowment that “the Trustees shall have power and it shall be their duty: ... To have taught in the University the right and advantages of

association and co-operation.”

I completed the article while at Duke University, where I got to know the preeminent historian of the Populists, Prof. Lawrence Goodwyn. I worked with Prof. Henry Levin, David Jacks Professor of Higher Education at Stanford University, on a proposal to bring Prof. Goodwyn to Stanford to give a Centennial lecture on Leland Stanford’s historical contributions in the context of the Populist movement. The Centennial Operating Committee rejected the proposal, claiming that the shared opinion of the committee was that “there just wouldn’t be much interest in the subject matter.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Tim Tyson, Prof. Henry Levin, Prof. Lawrence Goodwyn,

Prof. Barton Bernstein, Ted Nace, Herb Caen, Roxanne Nilan, and Bob Beyers

for their helpful comments, the staff of the Stanford University Archives

for their excellent and generous librarianship, and the Synergy and Columbae

cooperative communities for creating the intellectual environment that

gave rise to this work. Research for this article was initiated in the

Stanford Workshops on Political and Social Issues (SWOPSI), Stanford University.

NOTES

*

The original title of this article, “An End to Capitalism: Leland Stanford’s Forgotten Vision” was perhaps my response to the widely discussed 1989 article, “The End of History?” by Francis Fukuyama (The National Interest 16:3-18). In 1996 when I prepared this article for the World Wide Web, it seemed to me that “Beyond Capitalism” better reflected Leland Stanford’s actual vision. Stanford’s efforts were more about beginnings than endings.

↩

+

The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Volume II. James T. White & Company, New York. 1892. p. 129.

↩

1.

Bancroft, p. 112.

Bancroft’s posthumously published biography of Stanford

must have been completed between September 1889 and December 1889, based on information in Bancroft, p. iv, and in George T. Clark,

1933, “Leland Stanford and H. H. Bancroft’s ‘History’: A Bibliographical

Curiosity,” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 27: 12-23.

Bancroft does not cite the sources for his extensive section quoting Leland

Stanford on “the character and purposes of the university” (pp. 105-117);

part of it (not used here) is from an interview of Leland Stanford in

the San Francisco Examiner, April 28, 1887.

↩

2.

Stanford Observer 21 (5): Special Issue, April 1987. Stanford Observer 21 (6):

9-11, May, 1987. Campus Report [Stanford] , March 7, 1984, pp. 13-16.

Campus Report. November 13, 1985, pp. 1, 7-10. Sandstone and Tile 9 (2), Winter

1985. Sandstone and Tile 10 (1), Autumn 1985, pp. 1-11. “History of the University,”

Stanford University Bulletin 31 (79), September 1987, pp. 6-7.

↩

3.

Curl, pp. 5-21.

Adams and Hansen, pp. 11-18.

↩

3a.

Nordhoff, 1875, p. 11.

↩

4.

Goodwyn, pp. 25-93. Curl pp. 26-31. Adams and Hansen, pp. 16-18.

↩

5.

Stanford, pp. 1-2.

↩

6.

Townsend.

The formation of cooperative associations among the California gold miners may be a subject whose history has yet to be written. There are brief references to it in Shinn (pp. 111-114, 288-289), and it may have been a source fostering the formation of cooperative projects among California farmers afterward (Nordhoff, 1873, pp. 202-209).

↩

7.

Goodwyn, pp. 32-35.

↩

8.

Bancroft, p. 114.

↩

9.

Bancroft, p. 114.

↩

10.

Stanford, p. 4.

↩

11.

Congressional Record, 49 Congress 2 Sess.: 1804, February 16, 1887.

↩

12.

Stanford, p. 16.

↩

13.

Townsend.

↩

14.

Stanford, p. 3.

↩

15.

Congressional Record, 49 Congress, 2 Sess.: 1805, February 16, 1887.

↩

16.

Stanford, p. 4.

↩

17.

Stanford, p. 11.

↩

18.

Stanford, pp. 6-7.

↩

19.

Stanford, p. 11.

↩

20.

Stanford, p. 15.

↩

21.

Stanford, p. 11. The capacity of worker cooperatives to reduce unemployment

is also the subject of more recent studies, see Levin, H. M., “Employment

and Productivity of Producer Cooperatives,” in Jackall and Levin, pp.

21-24.

↩

.

22.

Stanford, p. 6.

↩

23.

Levin, H. M., “Employment

and Productivity of Producer Cooperatives,”

in Jackall and Levin (1984), pp. 24-28.

↩

24.

Stanford, pp. 15-16.

↩

24a.

Stanford, p. 3.

↩

25.

Bancroft, p. 112.

↩

26.

“Address of Leland Stanford to the Trustees,” in The Leland Stanford,

Junior, University, pp. 30-31.

↩

27.

Stanford, p. 4.

↩

28.

Stanford, p. 5.

↩

29.

Stanford, pp. 5-6.

↩

30.

Stanford, p. 6.

↩

31.

Townsend.

↩

32.

“The Grant of Endowment,” p.16 in The Leland Stanford, Junior, University, Stanford University Archives.

↩

32a.

Townsend.

↩

33.

Congressional Record, 49 Congress, 2 Sess.: 1805, February 16, 1887.

↩

34.

Townsend.

↩

35.

Townsend.

↩

36.

Stanford, p. 6.

↩

37.

Curl, p. 29.

↩

38.

Adams and Hansen, pp. 13-14.

↩

39.

Congressional Record, 51 Congress, 1 Sess.: 5170, May 23, 1890.

↩

40.

Goodwyn, pp. 86, 111.

↩

41.

Goodwyn, pp. 107-115.