|

M

A U I S T Y

L E

Environmental Heroes

by Helen

Gillette

Through the years, the natural environment of these Islands has

endured much.

Thankfully however, Maui is blessed with lots of public-spirited

volunteers who are out there doing what they can to make a

difference. Whether it’s reforesting, recycling, or protecting our

endangered species, these folks are saving and preserving our

environment one tree, one turtle, one landfill at a time. We’ve

selected just a very few to honor here.

With a Computer and Shovel

Photo: Ron

Dahlquist

In a scrubby gulch of a Kihei subdivision, two blocks from his

home, Lee Altenberg is busy planting a forest. In a scrubby gulch of a Kihei subdivision, two blocks from his

home, Lee Altenberg is busy planting a forest.

This gulch, running from the 5,000-foot level of Haleakala to the

Kama‘ole beaches, was once filled with native forest, most of

which was long ago trampled and eaten by cattle, and crowded out

by invasive species.

For about three years, Altenberg, a computer science professor

with the University of Hawai‘i, has been rooting out the

intruders, what he calls “all those Walmart weeds,” while

nurturing the few remaining natives, and planting new ones—already

more than 20 species that once thrived in this area.

Altenberg takes the cuttings and seeds from plants like naio,

koai‘e, wili wili, ‘a‘ali‘i and ‘ohai growing in the Palauea Beach

area south of Wailea, where planned development will further eat

into the remnants of the dry land forest there. He tries to

propagate the cuttings and seeds in his little backyard nursery.

When they’re sturdy enough, he transplants them at the gulch,

regularly returning to water and nurture them.

Through the years, Altenberg has been a working volunteer on a

number of reforesting projects, including the forest remnants at

Auwahi and Pu‘u O Kali, high on the flanks of Haleakala.

Along with shovel and hoe, Altenberg also uses the computer to

help save the native flora. His work with the university involves

investigating the theoretical foundations of evolution and

evolutionary processes. He says he went into this complex branch

of computer science because of its promise for making discoveries

that could help the world’s living conditions.

“As a kid I wanted to use computers to save the ecology, Altenberg

says.

“Now I just think that maybe we should try to do it one backyard

at a time.”

It would make a difference, he says, if neighbors started putting

native plants in their yards.

And if you want to help out in the gulches, Altenberg says “you’re

welcome to join ‘Lee’s Gym.’ Just come on over, and I’ll hand you

a pick.” You can call him at 875-0745.

Aloha Shares

“One Man’s Trash”

Joy Webster’s husband, architect Jim Hestand, used to come home

telling her about all the good, usable items he saw being hauled

to the landfill—lumber, light fixtures, furniture, fancy

appliances—items left over from building and remodeling projects.

Webster attacked the situation. Working through the Maui Recycling

Group, (she edits its quarterly Recycling Guide), Webster spent

months organizing a database of willing “donors” and nonprofits.

The effort is called “AlohaShares.”

“The aim,” she says, “is to keep usable materials out of Hawai‘i

landfills, and get them into the hands of our nonprofits, churches

and schools.” Nonprofits post their wish lists online at

www.alohashares.org. A business or individual with items to give

away posts lists of “give-aways,” and nonprofits consult the web

address to see what’s available.

The process is handled almost entirely by email. The first

nonprofit responding gets the item. The cost: nothing. There’s no

charge to anybody. Alohashares expenses are carried by the Maui

Recycling Group, which is not funded by the county. Expenses are

paid from grants, when they are available. Volunteers work without

pay. Any group or individual may join the donor group. Recipients

must be nonprofit organizations, churches or schools registered in

this state.

Toll-free: 1-866-542-2232 or www.alohashares.org

Labor of Love

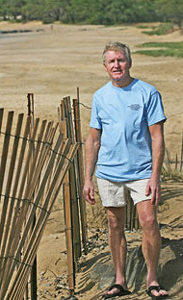

Down in the Kanaha Beach dunes, just off the Kahului Airport

runways, almost every morning you’ll find this big bear of a man

busy tending what he calls his “17-acre garden.”

For months now, retired Lahaina postmaster John “Mike” Perry has

been ridding the beach area of what he calls “scrubby, ugly

invasive plants” so that the “small remaining islands” of native

Hawaiian plants can spread.

He says that he finds that if he just eliminates the

Johnny-come-lately

stuff, the good heritage plants will gradually recover and expand.

“It’s a lot less work than transplanting tender little greenhouse

plants, and it works better.”

The beach area from the Kahului Wastewater treatment plant to the

airport’s edge already looks much better, with pretty little

pink-flowered naio and others spreading over the dunes.

A year ago Perry had already put in so many volunteer hours that

the county, under its Retired Senior Volunteer program gave him

its annual Tony Tomoso “Outstanding Volunteer” Award for 2002.

He’d chalked up over 1,100 hours that year alone. U.S. Geological

Survey botanist Forest Starr said the Kanaha restoration project

is especially significant because the area contains some of the

Islands’ last undeveloped coastal dunes.

Clearly, this is a labor of love for Perry. Not only does he not

get paid, he seems to be putting his own money into the project.

Perry never says no to volunteer help, so go on down and hunt him

up. Call him at 572-9836.

Honu 'Ohana

Photo: Ron Dahlquist

Everybody's

heard that our Hawaiian sea turtles need help. Of all the

hatchlings that crawl out of the nest, only about one in a

thousand makes it to maturity. There are lots of predators

out there, both on the beach and in the ocean. Everybody's

heard that our Hawaiian sea turtles need help. Of all the

hatchlings that crawl out of the nest, only about one in a

thousand makes it to maturity. There are lots of predators

out there, both on the beach and in the ocean.

Happily, the turtles have

some devoted human friends, a bunch of dedicated volunteers to

watch over them.

For instance, there's Maui

dentist Steven Williams. For the past seven years he has

coordinated the Turtle Dawn Patrol on the beaches from Ma'alaea to

Big Beach, taking turns with this band of 30-some volunteers -

among them, his wife, Esten, and their two daughters.

Early nearly every morning

during the June to October nesting season, they're out looking for

new turtle tracks, trying to locate freshly made nests.

After consulting with biologists, the volunteers mark the nesting

areas and then watch over them until hatching day.

Afterwards, they carefully excavate the vacated nest to count

eggshells and free any keiki who couldn't dig their way out.

Getting on with L.I.F.E.

Photo: Bill Korey

When Walter Kanamu goes hiking alone in the forest, he says he

feels his grandfather’s spirit hovering near, sometimes

whispering, “Save the forest.” When Walter Kanamu goes hiking alone in the forest, he says he

feels his grandfather’s spirit hovering near, sometimes

whispering, “Save the forest.”

Kanamu’s grandfather, William Kai‘aokamalie, would be just the

type to pass on that message. About 1939, he met visiting

botanist-explorer Joseph Rock during Rock’s second trip to Maui,

and took him around the island to see what was left of the

vanishing dryland forests. Rock, aghast at the destruction, urged

the Hawaiian man to do what he could to preserve the remains of

forests that had once covered the mountainsides.

When Kai‘aokamalie was a kid, ‘Ulupalakua was all canopied

forest. But he lived to see vast areas cut back for family farms,

ranches and sugar cane.

What was left was being encroached upon by animals and invasive

plants.

Kai‘aokamalie took Rock seriously and started fencing in Auwahi,

a forest fragment located on the outskirts of ‘Ulupalakua Ranch.

“I was just a young kid then,” Kanamu says, “but I remember. He

took my dad, my uncle and me into the forest”.

Kanamu, a Maui Community Corrections Center employee, says that,

in 1996, the old fence was still there, rusty and ready to fall

down, when U.S. Geological Survey’s research biologist Art

Medeiros was directing a band of volunteers in re-fencing Auwahi.

Kanamu and his cousins, Wally English and Ma=healani

Kai‘aokamalie worked with them.

“In 1995, my cousins and I established the first Hawaiian

nonprofit environmental organization: Living Indigenous Forest

Eco-Systems,” Kanamu says. And so began L.I.F.E.

Another cousin, Aiona Kai‘aokamalie, whom Kanamu says was the

“inspiration” for setting up L.I.F.E., had already passed away.

Now L.I.F.E. is concentrating on the forests on Hawaiian Homestead

Lands located high up on a slope of Haleakala. The organization

is headed by the three cousins.

Using $100,000 made available by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service for fencing and helicopter time, they’re putting in seven

miles of fence, from the area adjacent to Poli Poli and above

Kanaio to Manawainui Gulch, in order to keep out cattle, goats,

wild pigs and deer.

Lots remains to be done, Kanamu says, but they’re on their way.

To learn how you can help call Walter at 760-8224.

Friends of Keone‘o‘io

Down at La Pérouse Bay, you’re apt to see someone running around,

clipboard in hand, talking to people who are out picknicking,

kayaking and otherwise enjoying that remote bit of shoreline.

That person is likely to be one of the volunteers of the Friends

of

Keone‘o‘io, an organization set up in 1999 to protect that area

so rich in archeological treasures.

For four years the volunteers have been stationing themselves at

the beach, collecting human use data, handing out brochures

encouraging wise stewardship of the area, and doing all they can

to cordially educate people about the impact to this endangered

area from increased traffic by hikers, kayakers, snorkelers and

others.

It’s hot, dusty (unpaid) work, but worthwhile, say the volunteers,

now 100 strong. Others agree that the friends are doing good work.

The grassroots group has received several grants to fund

educational brochures and a Web site.

On most days you’all find one or more of the volunteers at an

information table near the beach spreading the word about the

historical and environmental richness of the bay. You can find out

more about the Friends of Keone‘o‘io by calling 808-870-6957.

|